In 1978, French racer Thierry Sabine founded an epic race. The Paris-Dakar was a marathon across Europe and Africa, which started at the foot of the Eiffel Tower and ended in the capital of Senegal, on the shore of the pink Lake Retba. It was the Grand Prix of off-roading. On the starting line were legendary men and powerful bikes, advanced enough to approach 200 km/h on dirt and sand tracks. There was Jean Claude Olivier and the four-cylinder Yamaha prototype, but above all Neveu, Picco, Lalay, Orioli, De Petri and Terruzzi, the factory Africa Twins and Cagivas with Ducati engines.

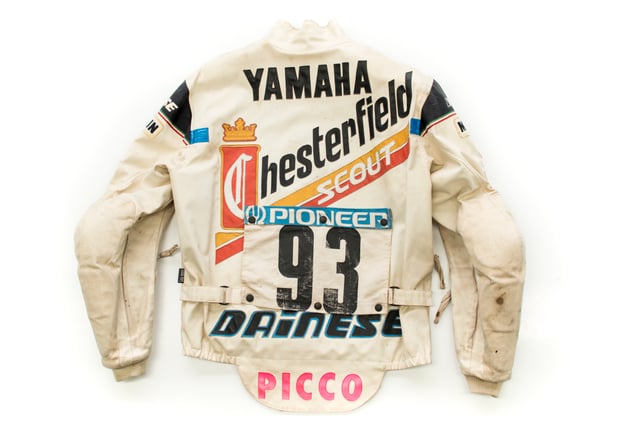

Here too, there was a need for protection, and Dainese got involved for twenty years. Track clothing affected enduro, resulting in clothes made specially for rally raids that became increasingly high-tech and specific. Initially there were mixed fabric-leather jackets, then tough modern fibers and rigid elbow and shoulder protectors. The integrated back protector was soon to follow, now essential in any sport on two wheels. Some of the jackets made for Edi Orioli, four-time winner between 1988 and 1996, used extremely sophisticated materials such as aramid and carbon composite fibers to protect the shoulders.

In the second half of the 1990s, the unthinkable happened. The hump on the back, like the one on Grand Prix suits, appeared on some jackets made for Orioli and a few others, in a very limited number. Here too, the hump initially had a protective function, to cover the cervical vertebrae, which back protectors couldn’t reach. Secondly, there was the desire to improve the aerodynamic drag coefficient. In a sport where going faster than 180 km/h was commonplace, sheer speed certainly counted for something. It could make the difference between a win and second place.

Dainese made different jackets and pants according to the weather conditions that the drivers were likely to encounter along the way. It even designed heated clothing to tackle the race’s opening stages. It started in the Paris midwinter and, as soon as it reached Africa, crossed the high mountain ranges of Morocco. In some stages of the competition, the temperatures were near or below zero. The race unfolded at the mercy of weather that didn’t stop short of ice and snow, which made the extra factor of how individual riders and equipment stood up to the cold something that could make all the difference.

It was here above all that Lino Dainese made the most of his inventiveness, to allow riders to give it their all in extreme environments. Special waterproof jackets were designed, made of Gore-Tex with heating elements woven in, as well as under-gloves and even heated boot insoles. Nothing was left to chance. The thermal jacket may have been worn over the racing one, but it wasn’t the same for the under-gloves. They had to guarantee the utmost sensitivity to the bike’s controls. The solution was to position the heating elements on the back of the hand, not the palm. That would have inevitably affected comfort and the quality of contact with the bar. The whole system was connected to a battery stored in a pocket. The amount of heat transmitted to the filaments could be adjusted using a simple potentiometer, with a scale of intensity from 0 to 10.

For the hottest rallies, such as the Rallye des Pharaons, lightweight, ventilated clothing was used instead. It was made with innovative fabrics and mesh inserts in areas less exposed to potential abrasion, such as the back of the jacket, the inside of the arms and the back of the knees, on the pants. The aim in all cases was to maximize performance and minimize risk.

Taking part in the pioneering period of the Paris-Dakar allowed Dainese to work and experiment with new technologies in the most extreme and challenging field. The know-how picked up over twenty years in Africa is now applied to mass-produced products available to all riders.