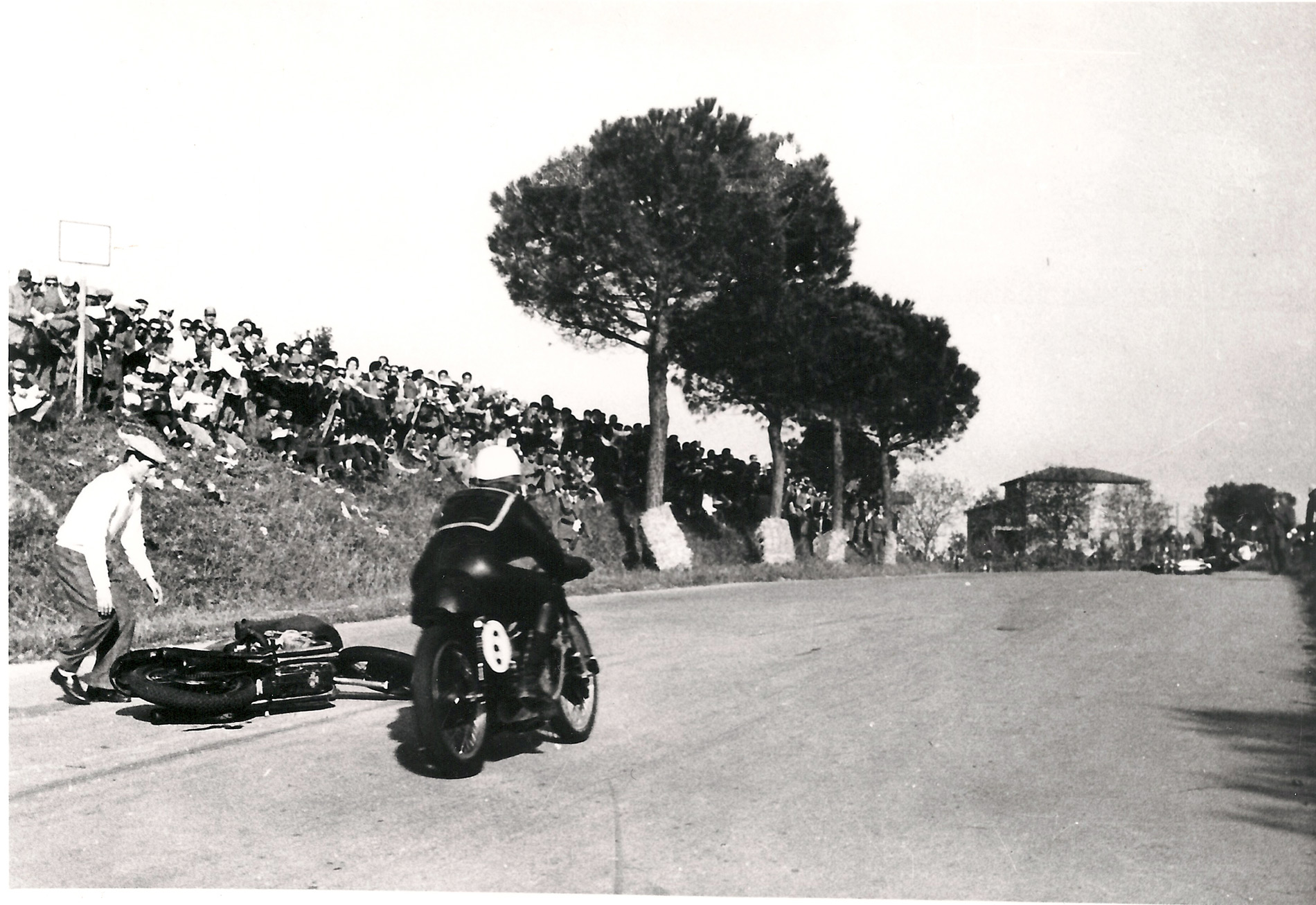

“It was April 22, 1957 and I was 16. The Autodromo di Imola had opened only four years before, and my father, Checco Costa, was among its founders. As the son of one of this new reality’s supporters, there were many doors open to me in Imola. I was in the habit of running round the pits, meeting the riders. That was all normal.

In the case of the 1957 Coppa d’Oro, however, the temptation to experience the race from a more exciting area was irresistible. I went to Acque Minerali, where my father wouldn’t have allowed me. My surname and my young, smiling face acted as very effective passes, and the supervisor let me in.

I saw the best riders of the age fly by from behind a tree: Liberati, Masetti, Duke. It was Geoff Duke, the British rider, who fell in front of me. I couldn’t just stand there watching. I flew onto the track to help him, pulled him to safety and then did the same with his bike. I wasn’t a rule-breaker anymore; I felt like a kind of hero who had saved someone special to him.”

This is the account of Claudio Costa, the most famous doctor in motorcycling history, best known to Italians as ‘Dottor Costa’. This incident in Imola made a deep impression on him personally, but caused an even greater change in the history of the sport.

“My father found out about it in the papers the next day, and it didn’t go as I might have hoped: not entirely, at least. I expected to be praised, but I got severely told off for breaking the rules, so severely that I started crying. But he did add, ‘This, Claudio, is what you will be doing your whole life.’”

It was a prophecy. The young Claudio Costa graduated in medicine 10 years later and shortly afterwards started working as a track doctor in his native Imola. He soon realized that the structure of safety management at circuits at the time was inadequate.

“The practice, up to that time, was to load pilots who had fallen into an ambulance and take them to the nearest hospital, but that meant that many died in the desperate rush. I wanted to change this completely. Help should have been going to the riders, not the other way round.”

Claudio Costa is a revolutionary, one with a clear vision and his feet firmly on the ground. Years later, his new concept of aid on the track was adopted by all circuits around the world.

“We provided the racetrack with everything it needed, but for as long as I was working in Imola I didn’t feel the need to go any further. I remember with pleasure the words of the great Barry Sheene, who said, ‘Try never to fall, but if you really have to, do it in Imola so Costa can save you!‘

Later, I started taking and offering my services to all the circuits of the world championship. The facilities I found myself working in were a far cry from what I had built up for myself in Imola, however. There was still a complete absence of organization.”

That was when inspiration struck Claudio. There should be a mobile clinic, an organized setting yet one able to move and follow all the races.

“A lot of money was needed to make my idea reality. Gino Amisano, the founder of AGV, helped me out. I knew him well because he was a very close friend of my father. Together, they gave rise to the spectacle that was the Imola 200, a race that brought the crème de la crème to the track. Amisano made an invaluable, essential financial contribution. He immediately understood what I needed, a clinic with intensive care and anesthetists, to stabilize the condition of riders before taking them to hospital.”

Costa’s Clinica Mobile AGV made its debut exactly 20 years after the prophetic episode in Imola, on May 1, 1977, at the Austrian Gran Prix in Salzburg.

“It was a baptism of fire. I had to deal with a disaster in the very first event. In the 350 race, Franco Uncini fell, and the accident affected other bikes, including those of Patrick Fernandez and Johnny Cecotto. We saved the lives of all three.”

These were only the first names on a list that was to include hundreds. From that moment, Costa’s kingdom started to gain ground.

“The Clinica Mobile also operated on another front. We were there to give help to the riders who needed it, but prevention is better than cure. We did a lot of work together with leading clothing and helmet makers.

AGV proved a real partner, rather than a sponsor only. Dainese proved open to us as well. Both Gino Amisano and Lino Dainese had the foresight to consider the Clinica Mobile as a kind of library, an invaluable archive of information that could be vital to the development of better protection.”

One example is gloves. At the beginning of the 1990s, not much progress had been seen in hand protection, and professional riders’ little fingers paid the price, a heavy one.

“The little finger is the most exposed part of the hand, the first to touch the ground and the one most likely to get stuck under the bike. There were often serious injuries with the gloves of the time, and treating such a small body part is incredibly difficult.

Firstly, we worked with Dainese on a glove with stitching that would hold up in slides on the asphalt. Secondly, we focused our efforts precisely on the little finger, because the other ones weren’t particularly exposed. We put as much protection as we could into this small space, going so far as to embed a metal anti-cut mesh between leather and inner lining.”

But Costa is someone who looks further ahead, whose solutions anticipate the problems. What could be done to lower the number of accidents? Easy, lower the number of falls. But getting riders to stop falling would appear to be impossible…

“I understood that protection alone wasn’t enough. Even an extremely effective protector is useless if it’s uncomfortable or bulky. If we dressed riders up in knights’ armor, they might be safe but they wouldn’t be able to ride.

Protectors, even before protecting, need to ensure freedom of movement. We could only hope to really increase safety on the track by making riders comfortable.”

You can ask any professional rider. One of the body parts subjected to the most stress when riding is the forearm. Violent acceleration, braking and using the clutch (when that was still relevant) are all essential movements that really put the rider’s resistance to the test.

“To begin with, the sleeves on suits were made entirely of leather, which is tough but not very flexible. Together with Dainese, we saw that the inside of the arms was an area not usually very exposed on falls, and we decided to try using stretch inserts. The new material allowed much freer blood circulation, more oxygen came to the muscle and its function was no longer compromised.”

We owe something more to Dr Costa. In the early 2000s, he made a major contribution to the development of D-air®, the first electronic airbag for motorcycling.

“I remember insisting on one thing in particular. The airbag had to activate before the fall, not after!

The airbag is something of a dream come true. It provides protection imperceptibly, until you really need it. And freedom of movement means the first, most infallible protection.”